– Patricia Smyth

courtesy of the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum

When we think about nineteenth-century panoramas of cities, it is most likely the triumphalist portrayals of the modern metropolis such as Thomas Hornor’s Panorama of London of 1829 that come immediately to mind. Hornor’s 360-degree painting, exhibited at the Colosseum in Regent’s Park, showed the contemporary city in an all encompassing view taken from the top of St Paul’s cathedral, but simulations of old London, featuring urban locations that had long disappeared, are less well known. These often appeared as part of a theatrical performance in the form of moving panoramas, long paintings unrolled on stage in such a way that the spectator experienced the sensation of moving through a long-vanished urban environment. They were a regular feature of nineteenth-century productions of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, for example, where, to musical accompaniment, the audience witnessed a journey down the Thames by barge through sixteenth-century London from Bridewell Palace to Greenwich.

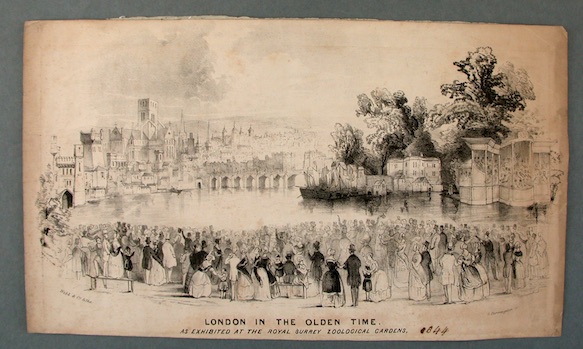

The old city could also be an attraction in its own right. This lithograph held in the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum relates to a show called London in the Olden Time, presented in 1844 at the Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens in South London, a pleasure ground and zoo in which visitors were invited to experience various ‘pictures’, as they were described. For one shilling, spectators could witness what was billed as a ‘daylight picture’ of London before the Great Fire, seen from the far bank of an artificial lake, mocked up to recreate the Thames. The scene was reportedly modelled and painted using 303,000 feet of canvas by the artists Danson and Telbin, who were both well-known theatrical scene painters, and was described as ‘correctly representing’ Old St. Paul’s, destroyed by fire in 1666, London Bridge, shown here with its shops and houses still intact (they had been removed in the 1760s), and ‘all the principal churches and buildings of the locality’.

The publicity also cited Baynard’s Castle, a medieval riverside palace that had also been destroyed in the fire, although fragments of it reportedly survived into the nineteenth century before being pulled down to make way for an ironworks. The site is now occupied by the brutalist office block, Baynard House. The entertainment didn’t stop there, however, since every evening visitors could experience ‘the most astounding exhibition ever yet offered to public notice, viz., a representation of the Great Fire of London, under the direction of Mr. Southby, the unrivalled pyrotechnist. Doors open at Nine, Feeding time for the Animals, Five. Conflagration at Dusk.’

Spectators, pictured here as well-turned-out family groups and including several children, gather in the foreground. At first it seems that they are excitedly pointing out the various landmarks to each other. A group to the left stand on a bench to get a better view, while to the right a small child is lifted shoulder height. But another version of this lithograph includes a further detail of the scene, which may in fact be the focus of their attention: General Tom Thumb, as the performer and impersonator Charles Stratton was known, ascending in a hot air balloon. In this print, you can just make out two men in the crowd pulling on a rope that rises like a kite string through the buildings in the centre of the composition. It is clear that those ropes are part of the mechanism involved in this additional attraction, which in the other image appears dead centre in the sky above the mock up of London’s north bank. A poster in the British Library confirms that Stratton did indeed on more than one occasion ‘go through the entire of his performances, on a stage prepared in front of the orchestra, and afterwards traverse the Gardens In a Balloon!’

With or without the added appeal of the ‘Lilliputian Wonder’, it is not difficult for us to imagine the lure of old London to this crowd of 1840s urbanites. Just like our own time, this was a period of accelerated transformation that saw the demolition of many ancient streets and landmarks under the banner of progress and modernisation. How blank and dispiriting are the widened streets and shiny new edifices that take the place of familiar sites, and how disconcerting it is, when some old building is destroyed, to find that, faced with the now vacant lot, we cannot even call to mind what was previously there. Immersive spectacles of old London allowed inhabitants of the modern metropolis to imaginatively experience the city of the past, the remains of which continued to disappear bit by bit around them. Such attractions naturally invited comparison with the contemporary environment. Like us, these Londoners appear fascinated by the spectacle of Old London Bridge with its houses intact. In fact, it is the relationship between the old city and the river that is really emphasised here. With its buildings opening directly onto the water, this is an urban environment still in harmony with the natural topography. This connection to the water was, of course, gradually eroded over the course of the nineteenth century, first with the building of the warehouses in the construction of the new docks at Wapping in the 1820s, and finally in the 1870s with the building of the Embankment.

The pre-Fire panorama presented to spectators at the Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens was, of course, no longer within living memory in 1844, but the ancient riverside came to symbolise not only what had been destroyed in 1666, but also the more recent losses associated with the programme of slum clearances and modernisation that cut swathes through old neighbourhoods. While the pre-Fire city was often represented as violent and disordered as well as insanitary and disease-ridden, it is nevertheless possible to detect a note of nostalgia in these evocations. Stage directions for the opening scene of Samuel Atkyns’ play The Fire of London; or the Baker’s Daughter, performed at the East End theatre the Royal Albert Saloon in 1849, cite a view of ‘London Before the Great Fire from the Southwarke side of the River Thames’, which would have been much like this one. The characters on stage in that first scene are religious zealots who deliberately set fire to what they regard as a hopelessly corrupted city, but at the start of the play, they nevertheless pause to admire the view of the riverside in an implicit invitation to the audience to appreciate its beauty. As one of the plotters laments, ‘to think that those goodly habitations, those towers, temples halls and palaces, should so soon be levelled with the dust’. The drama of old London going up in flames was an exciting enough proposition, but I think that in these careful reconstructions of a lost world there are some more complex emotions at stake – longing, perhaps, and the desire to restore, at least in the imagination, a connection to the past.